What is Benign Esophageal Disease?

Benign Esophageal Disease encompasses a variety of non-malignant (non-cancerous) diseases that can affect patients’ ability to swallow food and liquids in addition to experiencing pain and discomfort. At Saint John’s Health Center, we employ a multi-disciplinary, minimally invasive approach to develop highly effective treatment plans for patients with benign esophageal diseases.

We treat a variety of conditions including:

- Achalasia

- Barrett’s esophagus

- Esophageal cancer

- Esophageal diverticula

- Esophageal stricture

- Esophageal web

- Esophagitis

- Gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Hiatal hernia

- Zenker’s diverticulum

Types of Benign Esophageal Diseases

Esophageal strictures

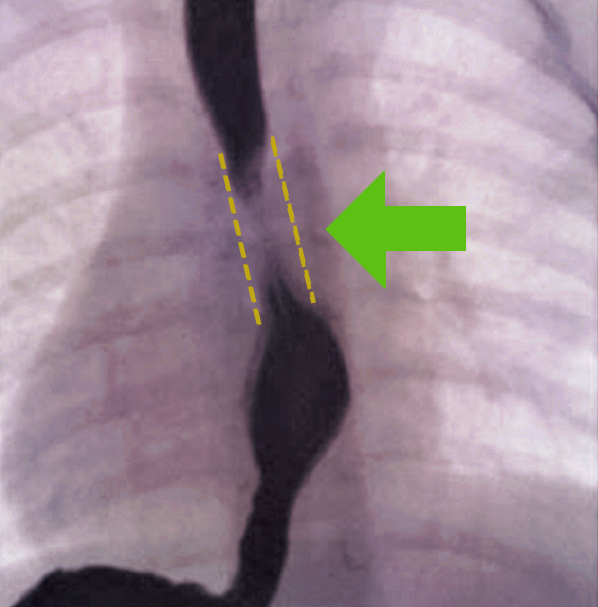

Esophageal stricture is a narrowing of the esophagus, which is caused by a problem within the esophagus or by compression from the outside. To diagnose esophageal stricture, the patient’s symptoms, a physical examination, imaging and endoscopy. If cancer is likely or suspect, pathology helps us determine the type of cancer and stage.

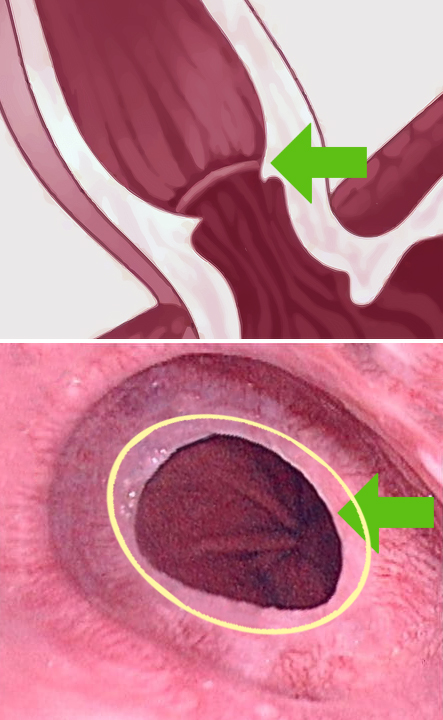

Peptic stricture

Acids from the stomach can back up into the esophagus causing scarring. A weak lower esophageal sphincter (LES), which work as a one-way valve, allows the passage of food but prevents the acid from the stomach back to the esophagus. A Hiatal hernia, which can also allow acid to regress, occurs when part of the stomach protrudes up into the chest through the diaphragm. This may result from a weakening of the surrounding tissues and may be aggravated by obesity and/or smoking.

Esophageal diverticulum

A diverticulum is an outpunching or sac arising from the wall of the esophagus which can contain one or more layers of the wall. Diverticula can be classified based on the number of intestinal wall layers involved.

Congenital esophageal duplication and duplication cyst

Congenital esophageal duplication originates from the primitive foregut. This defect is responsible for esophageal cysts and is the failure of proper development of the posterior division of the primitive foregut. Esophageal cysts are the second most common benign lesion of the esophagus. Most cases are diagnosed in childhood and are symptomatic. Cysts may become symptomatic in adulthood and are usually located in the right posterior mediastinum.

- Chest pain or chest discomfort is most common.

- Cough, stridor (a variable, high-pitched respiratory sound), tachypnea (rapid breathing) and other respiratory complaints due to compression from mass.

- Vomiting blood (Hematemesis) can occur if there is gastric epithelium within the cyst.

- Swallowing difficulties (dysphagia)

- Cardiac arrhythmias may also occur due to the compression.

Other complications may include infarction (tissue death due to inadequate blood supply) to the affected area, rupture, dysplasia, and malignant degeneration.

How do we diagnose benign esophageal disease for patients?

Diagnosis and determining the cause of the disease will determine the type of treatment needed. Difficulty swallowing (dysphagea) is the most common symptom. Frequently, patients will describe a progression of dysphagia from solids to liquids.

Determining the extent of esophageal disease using imaging

Imaging for benign esophageal disease includes a chest X-Ray, which may reveal a soft tissue mass or a cystic structure within the mediastinum. Barium swallow (esophagogram) is an imaging test that checks for problems in your upper GI tract that uses a special type of X-ray called fluoroscopy. This technique is utilized to help reveal esophageal compression and may also detect tubular esophageal duplication (a rare congenital anomaly that produces a second, smaller passageway within the esophagus). Computed Tomography Scan (CT) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) are also utilized, while an endoscopy helps to reveal compression of the esophagus.

Signs and Symptoms of Benign Esophageal Disease

Benign esophageal disease can affect quality of life, manifesting as heartburn and regurgitation of food and liquids back into the mouth. Most patients with Barrett’s esophagus have a history of heartburn and acid regurgitation. Less frequent symptoms include dysphagia (swallowing difficulties).

With esophageal disease, you may experience one or more of the following conditions:

- Chest pain

- Hematemesis (vomiting of blood)

- Cough

- Wheezing

- Melena (dark, tar-like feces)

Causes of Non-Cancerous Strictures of the Esophagus

Esophageal stricture is an irregular compression of the esophagus, which can reduce or block food and liquid flow to the stomach. Swallowing is difficult because it feels like food is stuck in your throat. GERD is the most common cause of strictures, but cancer and other issues can also cause them. A dilation procedure can widen the esophagus and reduce symptoms.

Stricture can be the result of:

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (gerd)

- Peptic stricture due to stomach acid

- Schatzki’s ring

- Motility disorder of the esophagus

- Autoimmune diseases (scleroderma, lupus)

- Immunocompromise

- Collagen vascular disease

- Crohn’s disease

- Infectious esophagitis,

- Hiatal hernia

- Caustic (swallowing toxic liquid)

- Congenital (born with the condition)

- Can be caused by some medicines

- Reaction to foreign body reaction

- Radiation therapy

- Cancer or benign tumors

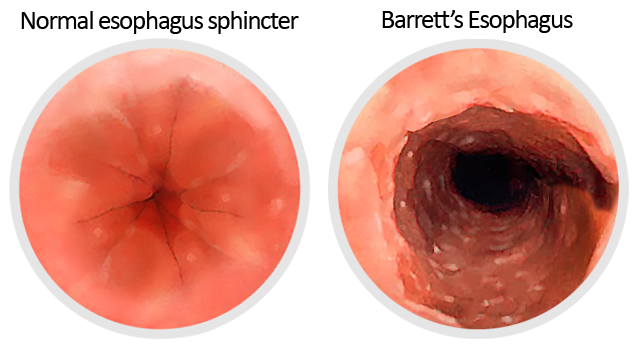

What are the risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus?

Barrett’s Esophagus is determined by endoscopy, examining the condition of the lining at the bottom of the esophagus.

Risk factors for the development of Barrett’s esophagus include:

- Found mostly in men

- Smoking history

- Obesity

- Caucasian ethnicity

- Ages 50 and older

- Greater than 5-year history of reflux symptoms

Esophageal motility in Barrett’s

- A weak, lower esophageal sphincter allows for pathologic reflux to occur.

- Esophageal constriction and relaxation is often impaired, exacerbating the delay in acid clearance from the lower esophagus.

- Chronic inflammation and fibrosis may lead to esophageal stricture, frequently at the proximal end of the involved segment.

Diverticulum Conditions

Diagnosis of esophageal diverticular: Pharyngeal – Zenker’s

Symptoms of esophageal diverticular may include:

- Aspiration pneumonia

- Halitosis

- Regurgitation

- Dysphagia, ranging from globus sensation to obstruction

- Bleeding

- Perforation

- Development of carcinoma within the pouch

- A mass in the neck if the diverticulum is large

Diagnosis may include the need for imaging services, including Barium swallow. This helps to visualize the entire region from the neck down. Lateral views demonstrate the extent of Zenker’s disease. Computed tomography (CT) scan is also utilized to improve the view of the esophagus and surrounding structures. Endoscopy is not always necessary in Zenker’s if the diagnosis has already been made via barium swallow.

Identification and diagnosis of esophageal diverticular: Midthoracic – Parabronchial

Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) is the most common symptom, but it is often due to an underlying digestive disorder rather than the diverticulum itself.

- Regurgitation

- Aspiration pneumonia (food or liquid is inhaled into the airways or lungs)

- May develop obstruction

- Bezoar formation (an indigestible mass)

- May develop carcinoma within the pouch

Physical findings may include the need for:

- Imaging

- Barium swallow

- Visualized in the chest

- Computed tomography (CT) scan may be done,

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD)

Imaging can help in identify erosion or other endoluminal pathology that may be associated with or the cause of the diverticulum.

Identification and diagnosis of esophageal diverticular: Epiphrenic

Epiphrenic is usually asymptomatic, while dysphagia is the most common symptom, but it is often due to an underlying digestion disorder in patients rather than the diverticulum itself.

- Regurgitation

- Aspiration pneumonia

- May develop obstruction

- Bezoar formation has been described

Physical findings in the patient may include the need for:

- Imaging

- Barium swallow

- Visualized near the diaphragm

- Computed tomography (CT) scan may be done

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), which allows for Visual inspection of the esophagus.

Identification and diagnosis of esophageal diverticular: Intramural pseudo-diverticulosis

- Dysphagia is the most common symptom.

- May have esophageal dysmotility.

- May be associated with esophageal stricture.

Physical findings may include the need for:

- Imaging

- Barium swallow

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD)

Benign Esophageal Disease Treatment Summary

The goal of treatment is to restore the ability to swallow normally. Initial therapy usually consists of esophageal dilatation, however, medical therapy is needed to promote healing as well as to reduce the chance of recurrence.

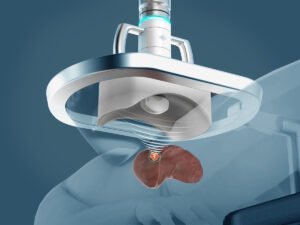

Endoscopy

Treatments will require endoscopy in most cases. Endoscopy involves inserting a thin tube into the esophagus that allows us to view the passageway and stomach. Endoscopy services are a common medical procedure in health care that allows a doctor to observe the inside of the body without performing major surgery. Endoscopic procedures include confocal endoscopy, ablation, and endoscopic mucosal and submucosal dissection. Endoscopy is also referred to as an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, which is equipped with a small camera at the end of a long, flexible tube. This is the primary tool used to diagnose and sometimes treat a variety of conditions that affect the upper part of the digestive system in patients.

Medical therapy

Proton Pump Inhibitors (medicine that reduces the amount of acid produced in the stomach). This helps to reduce the need for dilatation services.

Dilatation

Under visualization by the EGD, a catheter with a balloon on the end is passed through the stricture. The balloon is inflated slightly to help open the narrow area. Other kinds of dilators can be used which are also passed from the mouth through the stricture in the patient’s esophagus.

Stents

Stents are most used in patients with dysphagia (problems swallowing) due to cancer. Stents are both permanent and removable for patients.

Surveillance

Patients with Barrett’s Esophagus may require regular endoscopic surveillance. The goal is to identify any changes in the ability or inability to swallow solid food and liquids or the progression of cancer ,which is determined by a biopsy.

High-grade dysplasia

High-grade dysplasia is known to be associated with the development of adenocarcinoma (cancer of the glandular structures in epithelial tissue). Approximately 10-28% of patients progress from high-grade dysplasia to adenocarcinoma within 5 years. Unsuspected cancer has been found in 33% to 45% of patients with Barrett’s esophagus who underwent esophagectomy for high-grade dysplasia without pre-operative evidence of carcinoma. Commonly, patients with high-grade dysplasia should undergo endoscopic surveillance every 3-6 months.

Learn More

Click here to learn more about Click here for Benign Esophageal Disease Treatments.

Call today to learn more about Benign Esophageal Disease and diagnosis. Our multi-disciplinary team is ready to support you.

If you have questions about benign esophageal disease, please call today. Click here to request an appointment.